It hit me at the Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan concert.

Willie’s 92. Dylan had just turned 84 that day. Neither one really sings anymore - they talk their way through the songs now, with a rhythm that’s half melody, half memory. But it’s still powerful. It makes you feel time passing - not in years, but in meaning. And somewhere in the middle of Under the Red Sky, as Dylan half-sang, half-spoke, I realized something about my dad.

He used to say my sons’ names like a little spoken song. Even when the dementia had taken almost everything else, he still had that. He’d forget who I was, now and then, but he never lost the rhythm - Arlo, Louie, Sully - said in that order, every time. Like a tune he could still play. I don’t know if he meant to hold onto it, or if it was instinct. He’d built systems his whole life - as a professor, a bioengineer, an inventor. Maybe this was one last quiet system. A rhythm that helped him remember what mattered.

He passed away on November 3rd. That was the week I’d planned to start harvesting my dahlia tubers - something my folks and I had joked about years before. I’d said, half-laughing, “Just don’t die during harvest or shipping season.” As they both got older, and their minds started to drift into fog, the joke drifted off too. But I guess some part of him remembered it. Or maybe life just has a timing all of its own.

I got the call from my cousin two days before he passed. She said I should come. That my dad had decided to go to sleep. That it might take a week. But it didn’t. He slipped away an hour before my plane landed in Glasgow. I’d just entered Scottish airspace. I knew the second I saw my cousins’ faces at the gate. They didn’t need to say a word.

There’s a particular grief that comes with living an ocean away. You carry it from the start - the chance you won’t make it back in time. That’s why I kept my UK citizenship. So if the call ever came, I could run straight through the airport and get to where I needed to be. No customs line. No delay. I planned for that. But I still missed him by an hour.

The harvest had to wait. November disappeared into flights and jet lag and the disorienting quiet that follows death. I stayed in Scotland most of the month. Glasgow looked the same but didn’t feel like home anymore. When I finally got back to the farm, winter had already arrived. I started digging - cold mornings, wet soil, short days. No music this time. No podcasts. Just the work.

Tubers don’t wait. They don’t care that your dad just died. They need to be lifted, cleaned, divided, stored. Farming doesn’t stop - not for grief, not for anything. And so I worked. December into January. Then on to dividing, labeling, planning. It got done, but I can’t say how. Maybe years of repetition and muscle memory, carrying me through on autopilot.

Even a few days of illness can throw a farm out of rhythm. A month of absence does more than that - it makes everything unfamiliar. And the slow fog of grief is worse. It dulls the drive. For months I moved at half-speed. Looking back now, I think I’m only just beginning to catch up. Eight months later, the place is finally starting to feel like the farm again.

Midsummer Day was his birthday. I found myself walking the woods, following an animal trail past the cottonwoods and tall briars into the quiet darkness of the summer forest, where all the light had been gathered and held by the canopy above. I said his name out loud - maybe for the first time since he’d passed - wishing him a happy birthday. The sound drifted off into the branches. It felt good to say his name. Like turning a thought into something real - a sound wave moving through the air, brief but physical. Grief stays mostly in the mind, but speaking gave it shape. A small moment of weight and direction.

There’s a rhythm to farming. You can’t help but feel it - it gets into you, until it becomes part of how you move. The plants keep growing. The chores always need doing. You come back to the rhythm, even if your heart’s not in it. Grief doesn’t interrupt it - it just folds itself in, sits beside you while you work. Some days it’s invisible. Other days, it’s more present.

And that’s what I’ve held on to - the rhythm. Just like the one my dad used to say the boys’ names in. Simple. Steady. Even when the rest of him was fading. There’s something in that. Something that stays when everything else goes.

Like Willie sings, “It’s not something you get over, but it’s something you get through.”

So I slip into the rhythm and keep moving.

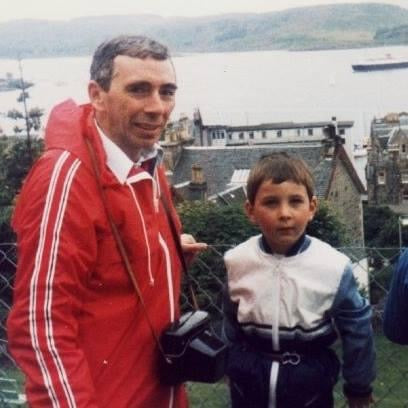

Frank Bell

Frank Bell

June 20, 1939 - November 3, 2024